The psychedelic history of remote-controlled orgasm.

WORDS: CHRISTOPHER TROUT | ART: PHILOTHEUS NISCH

This article is featured in Gossamer Volume Seven: the Touch issue—pick up a copyorsubscribe here.

In an undisclosed location, on a day like any other, a young man will lie back in bed, legs spread, broadcasting his body to an audience of thousands. He will be naked except for the wireless keyboard that occasionally covers his crotch and the limp pink silicone antenna that hangs from between his tight, hairless ass cheeks.

At any moment, a collection of anonymous onlookers will flood the room with a chorus of digital tokens. When they do, the young man’s smooth glutes will contract, his hips will buck skyward, and his body will convulse as if from electrocution. He will cry out as the coins pile up. On any given day, this scene will play out hundreds if not thousands of times, thanks to the advent of remote-controlled sex toys.

The whole thing might seem unremarkable today, but back in the psychedelic ‘60s, a “fuck-by-phone machine” was about as far out as you could get.

During the pandemic, sites like Chaturbate and Flirt4Free became unlikely hubs of intimacy when physical connection was at a premium. Isolated from others, discouraged from embracing the ones that we love, we turned to machines for companionship. With real-world institutions closed, our lives played out online. We searched our screens for education, for entertainment, and, perhaps most desperately, for affection.

The concept of a global network of electronically-connected, haptic sex toys has existed, at least in theory, since 1974 when the philosopher Ted Nelson wrote about a device devised by a young inventor named How Wachspress. The Auditac Sonic Stimulator, as it was called, used a combination of hi-fi audio equipment and repurposed household objects to turn sound into touch. For a couple of years in the 1970s, it became an unlikely media sweetheart, inspiring journalists, philosophers, and sex toy manufacturers to imagine a future where frictionless, computer-assisted intimacy could be had at a distance. The whole thing might seem unremarkable today, but back in the psychedelic 60s, a “fuck-by-phone machine” was about as far out as you could get.

It was 1969 and the internet was still the stuff of secret military projects. The Civil Rights and anti-war movements were gaining momentum, and young people all over the world were heeding the call to turn on, tune in, and drop out. They experimented with psychedelics and free love; they sought enlightenment from Eastern religion; and they embraced the sounds of electrified music. It was against this backdrop that Wachspress set in motion the chain of events that lead to what we now call teledildonics.

Wachspress was working on Manhattan’s Lower East Side as an audio engineer when, he says, he met an Afghan hound named Sylvie who introduced him to the owners of Cerebrum, a sort of multi-sensory, clothing-optional playground for adults. He soon began working there as a guide, walking patrons through a series of exercises meant to engage all the senses. Inside the sensorium, hippies in flowing white gowns played with mirrors, parachutes, and giant balloons. They ate marshmallows and rubbed Jergens on strangers’ bodies. They engaged with video projectors, sound baths, and scent diffusers.

Cerebrum closed after less than a year, but Wachspress’s time in the sensorium ushered him into a period of experimentation and exploration. He studied hydraulics, pneumatics, sensory substitution, and the resonant frequency of the human body. He also began experimenting with tuning forks for foreplay.

“It was a wild time, people were trying anything,” Wachspress would told Rolling Stone in 1974. “And it was at that time that I got the original acid flash of multimedia. The idea of two-way tactile communication over a distance. Carrying it to its most outrageous extension, a fuck-by-phone machine.”

It was a new way of experiencing the world, a paradigm shift for feeling, a portal to what he called “hyper reality.”

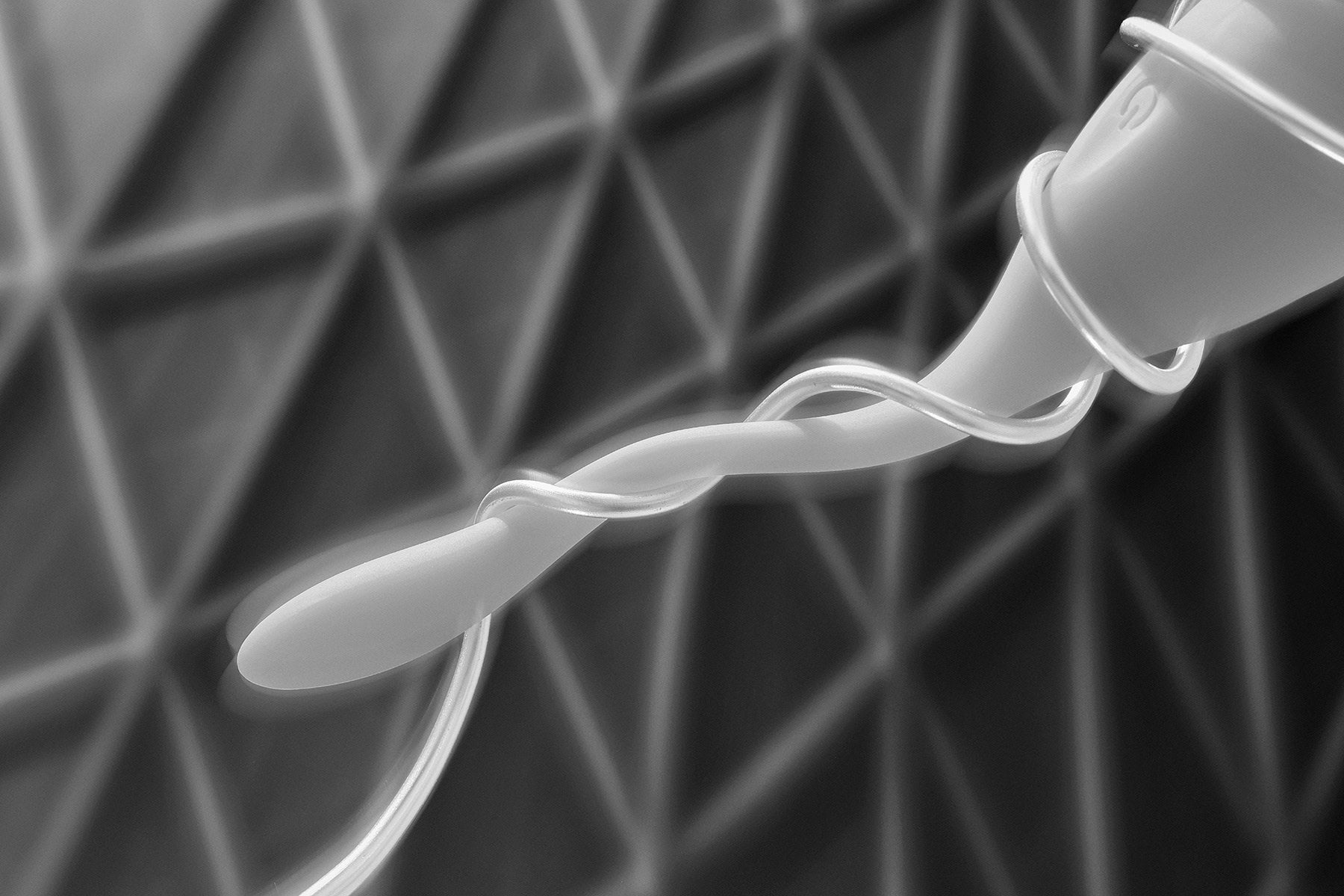

People called it a “sonic dildo,” an “audio transdoucher,” and a “pleasure machine.” It could be used for “sensory substitution, the generation of body music, pleasure stimulation, biopotential, physiotherapy, the generation of a new media for new perceptions, and as a part of multimedia experiences.” It also produced mind-blowing orgasms.

Wachspress marketed the Auditac as a hi-fi sex toy, but he saw it as more than a conduit for pleasure. It was a new way of experiencing the world, a paradigm shift for feeling, a portal to what he called “hyper reality.” Wachspress believed that humans could engage the senses to reach a heightened state of awareness. “Like making adjustments to a television set, except you’re what’s plugged in,” he told Rolling Stone.

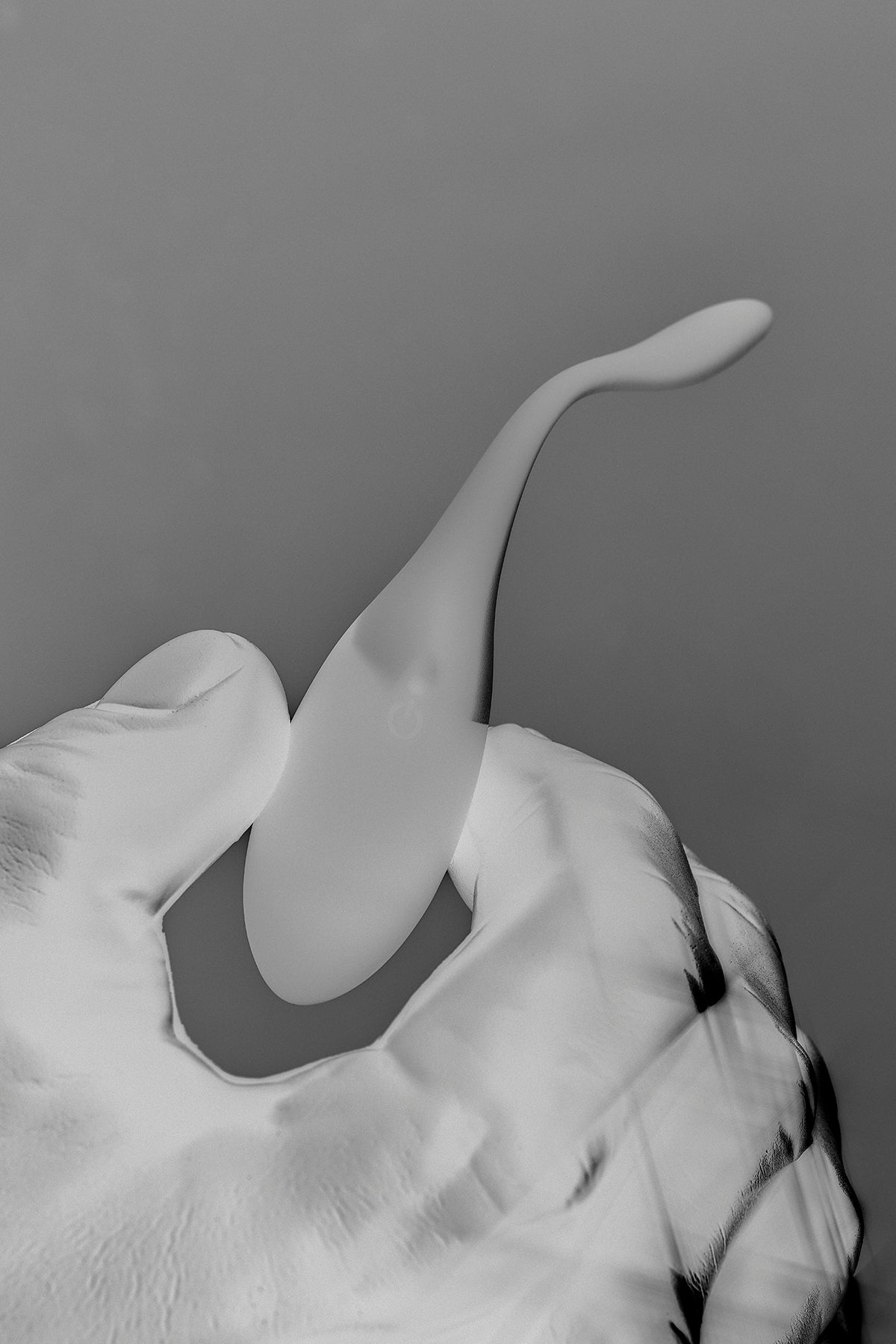

For all of the hype, the Auditac wasn’t much to look at. It was a simple, black box, containing an amp and a speaker, that carried sound waves down a clear plastic tube to any number of attachments that could be placed on, inserted into, or penetrated by the “listener.” New Age platitudes aside, it made you “feel sounds” the same way a loud speaker could, but in relative silence.

It would be easy to dismiss the Auditac as an over-engineered vibrator if it weren’t for the reviews. To the people who experienced it, the Auditac was a revelation.

On a foggy summer night in 1972, Wachspress gave the first public demo of the Auditac in the basement of Glide Memorial, a Methodist church in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. Members of the National Sex Forum, an offshoot of the church’s community outreach efforts, organized the exhibition as part of a radical sex ed program called Sexual Attitude Restructuring.

The demo created a small media storm that would last a couple of years and culminate in 1974 with the publication of Ted Nelson’s Computer Lib. Nelson focused on the device’s metaphysical potential, speculating that the “Wachspress machines may be an unfolding-mechanism for the unfeeling tightness of Modern Man.” But that night, in a church basement, the Auditac Sonic Stimulator excelled as a sex machine.

Writer Richard Neville captured the scene, describing one eager volunteer’s experience for The London Evening Standard. “The woman is caressing her body with the hose, or rather probe, which is releasing a throaty, semi-audible hum. She reports—and displays—heightened sexual sensation … By now the volunteer is relating to the machine in a manner that defies description here,” Neville wrote.

In a telephone conversation this past May, Wachspress explained that he used a combination of synthesizer improvisation and pre-recorded tracks to arouse volunteers, who he says “were flopping around like fish having super orgasms.”

Earlier accounts of the first demo went into more graphic detail. One male volunteer recalled “the most gorgeous orgasms in the world without erection or ejaculation” in the March 1974 edition of Hugh Hefner’s Oui. “I put it on my cock, and they started the machine going—and I just went into all kinds of beautiful orgasmic stuff,” he proclaimed.

The Sonic Stimulator had the world talking, but Wachspress had bigger plans. In 1974, he performed his most ambitious experiment to date: In the presence of Oui reporter Patrick Carr, Wachspress fulfilled his original vision for a fuck-by-phone machine. He rigged two Sonic Stimulators up to the phone line, carrying audio signals from an assistant’s vagina to his penis from across his cramped and cluttered San Francisco apartment. He called this application the Teletac, and declared the experiment a success.

The press from Wachspress’ first demos led to a residency at The Orphanage, a San Francisco nightclub where curious attendees could get a taste of synesthesia minus the mind-blowing orgasms. According to Wachspress, the club couldn’t afford the insurance to cover an uncensored show, but the spectacle was apparently no less enticing: An account of a decidedly PG-13 demo at the Orphanage that appeared in the Los Angeles Times was quickly syndicated across the United States.

One year later, in April 1975, the U.S. Patent Office granted Wachspress the patent for an ”audiotactile stimulation and communications system,” but the Sonic Stimulator would never live up to the hype. It fell into obscurity before ever hitting shelves. Wachpress says that his invention suffered due to bad timing among other factors. He believes retailers were reluctant to take on a sex machine because of the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Miller v. California, which set a three-pronged approach to identifying obscenity and gave states more leeway in prosecuting illicit behavior.

“We had distributors, we had reps, but it was always the same problem,” he said. “Customers liked it, salesmen liked it, but the owners were afraid. They’re still afraid of the sex thing.”

His brilliant machine, full of potential and capable of shifting human perception, was gone—but not entirely forgotten.

There just wasn’t enough money in it for Wachspress, who abandoned his sex machines for more palatable pursuits. In 1989, he was granted the patent for a “free flying magnetic levitator,” which he says makes for more polite elevator conversation. Still, he is reluctant to talk about his work in levitation, citing government classification. In the end, he says neither of his prized inventions ever amounted to much.

In conversation, he alluded to but said he couldn’t expand on one particularly difficult period, in which he says he “lost everything,” including his prototypes and audio equipment at auction. His brilliant machine, full of potential and capable of shifting human perception, was gone—but not entirely forgotten.

Eighteen years after the Glide Memorial demos, the futurist Howard Rheingold picked up where Nelson left off in Computer Lib, tying Wachspress’s vision of sex at a distance to the emerging field of virtual reality, and coining the term “teledildonics.” Rheingold’s essay, much of which first appeared on early social network The WELL in 1990, depicted a far more elaborate future than anything Wachspress had imagined.

Rheingold predicted that 30 years on, in the year 2020, anyone with enough money could jack into the telephone network, using a sensor-laden body suit and a VR headset to have sex “at a distance in combinations and configurations undreamed of by precybernetic voluptuaries.”

“You run your hand over your partner’s clavicle, and 6000 miles away, an array of effectors are triggered, in just the right sequence, at just the right frequency, to convey the touch exactly the way you wish it to be conveyed,” Rheingiold wrote.

Today’s “smart” sex toys, while inspired by Rheingold’s vision, are still pretty rudimentary. They may enable tactile intimacy at a distance, but they can’t mimic the feeling of a lover’s collarbone, and they most certainly have not inspired the great shift in consciousness that Wachspress and Nelson anticipated.

Wachspress is now “very old,” by his own account, living with his wife in San Francisco and working on research that he claims is classified. Today he seems defeated, a largely unrecognized inventor of unwanted machines, disillusioned by a world more worried about the bottom line than higher consciousness. He’s unable or perhaps unwilling to recognize the Auditac’s outsize impact.

Sex toy sales and camsite traffic hit record highs last year, introducing people all over the world to new ways of feeling at increasing speeds. In thousands of cam shows broadcasted every day, a new economy of touch is unfolding where performers have agency, and digital intimacy extends beyond screens. Humans now bridge great distances with a closeness once reserved for in-person affairs. This is all due in part to Wachspress’s belief that swapping one sensation for another could revolutionize the way that we perceive the world.

Yes, the Auditac is dead, but the digital coins piling up in chat rooms across the worldwide web still ring with possibility.