The fashion activist on building sustainable systems, raising kids honestly, and finding a place to put down roots.

AS TOLD TO GOSSAMER

This Conversation was done in partnership with our friends at Buffy, and appears in Volume Four of our print magazine. You can pick up a copy here or at a stockist near you.

I ended up here sort of by accident.

I was in Montreal working in digital literacy, access to information, and open knowledge —a lot of peer-to-peer education. It was oddly similar to what I do now in the fashion space. I had a blog about interaction design and information architecture. Someone at an agency in New York was familiar with my blog and was hiring, so I got the job here.

I was living in Montreal because my family and I escaped the war in Lebanon when I was four years old. In 1995, when the war ended, my parents and I moved back to Lebanon. So half my life was Lebanon, Montreal, Lebanon. But when it came time to continue my studies, my parents insisted I go back to Montreal because it was a freer education and would give me access to a lot of things I couldn’t otherwise have access to.

I’m very much a web native. It’s in my DNA.

I studied computational arts and interaction design—basically using technology and art to create responsive and immersive environments. Making dolls that can react to touch and play videos, or making a whole room interactive according to someone’s proximity to the walls.

But in 2006, on the day I was leaving to go there, another war started in Lebanon. I got a phone call from my mom at six or seven in the morning, and she said, “You won’t be able to come today because they shut down the airport and there are bombings.” And then the line cut out.

That whole summer, there was a war between Lebanon and Israel. At the time, I was working a lot with video—mash-ups, found footage, video art installations, and such. So I recorded CNN on VHS—I still had a VHS recorder—and I put my mom’s voice on top of it, so CNN was muted. That installation was my last piece.

With the war happening in Lebanon, I thought to myself, “Okay, I need to work. I need to actually do something that’s in the realm of working, because I’m now an artist and that’s crazy. What if my parents need to come here and I need to support them?” So I made a conscious decision that summer to stop doing arts and go more into design.

Translating complex information into something easy to understand was what I did as an artist, so I got a job with an agency working with lots of large databases of video and using design as a tool for social change. During the Arab Spring, I did a lot of work on digital literacy and access to information. The internet was shut down, so I focused on campaigns around accessing data. Later on, the group I was working with was working a lot in Syria, during and after the war. A lot of historical sites were destroyed, and so the same open knowledge movement was used to rebuild Palmyra—to rebuild the archeological sites, but in the digital space.

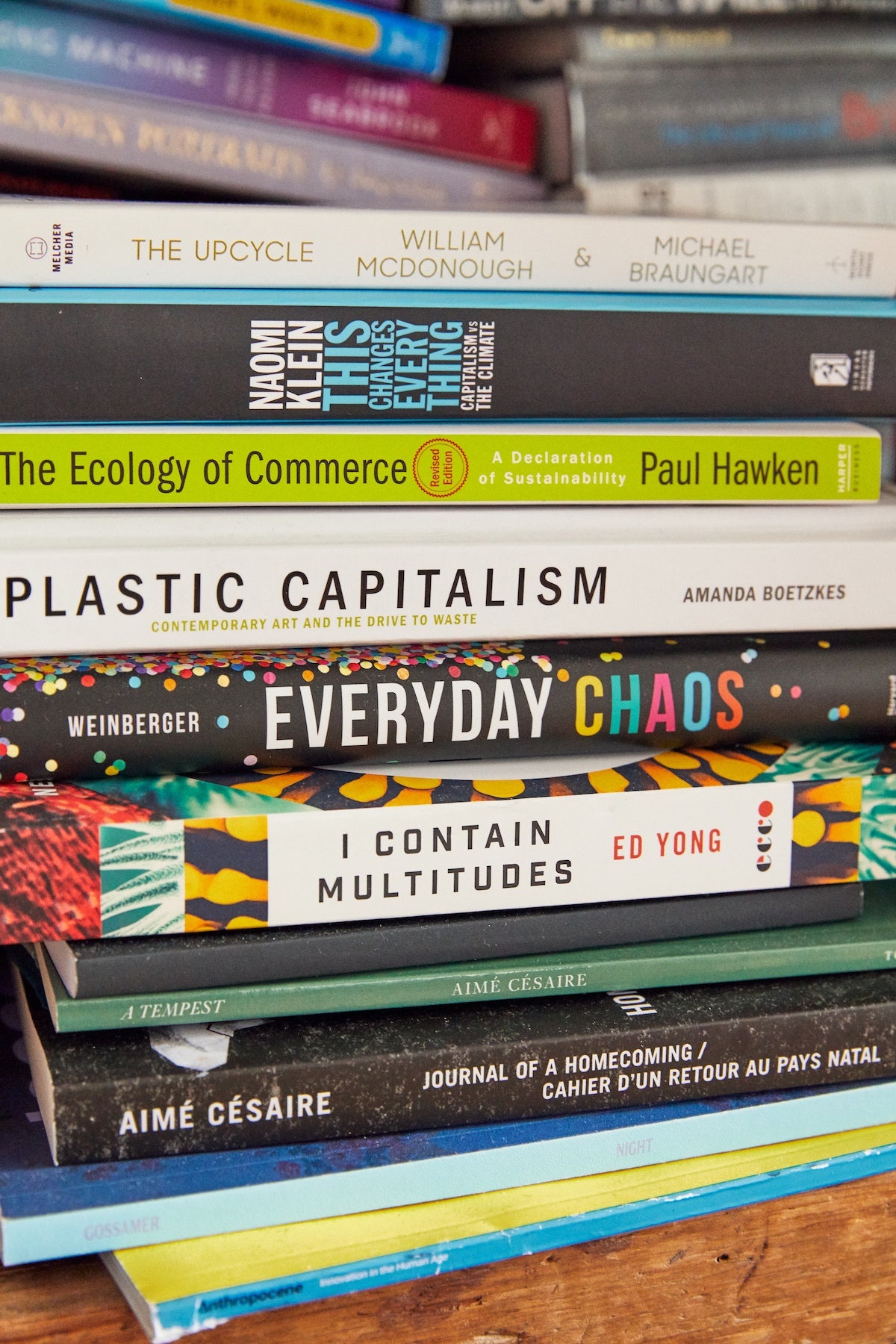

I’m very much a web native. It’s in my DNA. So when NASA made their data and imagery publicly available, I thought to myself, “Wow, these things need to be used. We need to materialize the immaterial. We need to materialize these open data images, because they are about the Earth; they are about the environment and this information needs to be accessible.” I came up with the idea of printing them on fabric, so that people could quite literally wrap themselves with this information. That was the start of Slow Factory.

It took me two years to research how I was going to print them in a way that wouldn’t impact the environment or human rights, because the two are very much intertwined. So, I researched what materials I was going to print these images on and where they were going to be made, and that’s how I accidentally stumbled into fashion: by looking at the systems behind fashion, the systems in which the fashion industry operates.

The fashion world did not have any kind of transparency, because luxury thrives on opacity.

At the time, the fashion world did not have any kind of transparency, because luxury thrives on opacity. I was like, “Oh my god, this is so corrupt.” Yet, culturally, it was considered totally fine—business as usual.

My research gave me a lot of awareness around supply chain and colonialism—and what the economic reality of both is today. The supply chains are based on the same routes, essentially, as colonial routes. I started talking a lot more about activism in fashion, and the link between the two of them. And also about the politics of fashion, about where we’re sourcing these items. I realized that what I was actually doing was sustainability literacy. So I started a conference called Study Hall, and I continue to work on that and Slow Factory.

I eventually chose a square piece of silk fabric on which to print these images. We used photographs that were part of NASA’s Images of Change, which show the Earth before and after. Fashion as a medium creates meaning. Whatever you wear, whatever the item is, it has a meaning. And meaning creates culture. What we observe, of course, is what culture creates, which can mobilize people. It can create movements. So, from that train of thought, I started thinking about fashion as a tool for activism.

There’s no such thing as a neutral piece of clothing, because even a white T-shirt has a meaning. Where that T-shirt is made has meaning.

When I first started, people thought the two concepts were way too far from each other. “Fashion is about luxury. It’s about the dream. It’s frivolous.” But I argued that no, fashion is an accessible form of art. It’s a utilitarian piece of art. You cannot walk around naked. You have to wear something, and there’s no such thing as a neutral piece of clothing, because even a white T-shirt has a meaning. Where that T-shirt is made has meaning. The cotton industry is very much related to slavery in America, and to the British Empire. It’s not neutral. Nothing is neutral. And nothing is objective.

This is a concept I talk about a lot because objectivity is a form of oppression. Because if you look at objectivity, what is neutral and objective if not the white gaze? If not white supremacy, then the whiteness of, for instance, Western philosophies which introduced this notion of neutrality. “This is neutral, and everything else is colorful and different and strange and we must study it, or we must exploit it.”

Western philosophies have designed the very systems in which we operate. So for instance, we create something, we use it, and then we discard it. And the shorter the timeline the better, because then you repeat that infinitely, and that’s what capitalism is.

We create something, we use it, and then we discard it . . . That’s what capitalism is.

Slow Factory has evolved in recent years, specifically since our collaboration with the United Nations, and is becoming more of an agency/lab. We do a lot of experimentation and research in terms of new materials and consumer perception—awareness is key in introducing innovations. We’re starting to work with a lot more solution providers, and also brands who are curious and interested in funding the research that we need to find these answers—and to incorporate them.

Oftentimes, the brand is aware of a solution, but their system is such that they cannot implement it, so how one implements solutions sustainably is also something we work on. There are costs. And not just monetary costs. There are human people that work within the supply chain that are going to be affected.

So how do we change them? The reason we can’t have innovations infiltrate the market is because the system is so heavily reliant on one resource. For instance, I think hemp is an incredible fabric for many properties. It uses way less water. It’s important to look into it as an alternative to cotton and there are a lot of designers out there who are already using it. But it’s also important to start looking into recycled fabrics and fibers, because we tend to go for just one solution—and one solution only. We have to diversify our portfolio of solutions. Otherwise we are going to run into the same problems that we have now, which is all the eggs in one basket, which is oil.

Now I have the privilege of being inside. Now, brands are like, “Okay, we heard you. Come in. What would you do?” And that’s when Slow Factory became more of an agency. Now I can bring my team in, and we can assess how we’re going to create change at scale.

It all goes back to my roots in system design. For several years, I felt like a geek trying to fit in with the cool kids. And I failed at it miserably—many times—because I felt like I lost myself entering into fashion. I tried to appear as if I didn’t care. “I’m not a geek, I’m like you!” But, no, I am who I am. I am a researcher. I am someone who is going to study things. I’m going to be writing thoroughly about them. If it’s not cool for you, then fuck you. My awareness has developed into accepting who I am: someone who does not come from fashion, but who is bringing a breath of fresh air into it and kicking the door open, shining a light into these dark, old colonial systems that need to be changed.

We are human beings fighting against a large system that’s way stronger than we are.

I have my own trauma coming from my own place of war and exile. Like a lot of people, I live with a lot of pain. So, from a very young age, I have explored healing in an experimental way. I can tell you: how I cope with trauma is through healing. Healing and care are the most important things we can do to and for ourselves.

I have a lot of peers who are activists in different fields. Gun control, racial justice, all sorts of inequalities. It’s crazy: we are human beings fighting against a large system that’s way stronger than we are. So we talk a lot about self-healing.

I had two back surgeries in 2016 as a result of the psychological weight I was carrying on my shoulders. Another activist peer of mine also had two back surgeries. I am surrounded by activists who suffer from so many physical illnesses, emotional illnesses, and, for some, intergenerational illnesses. Learning how to heal yourself is important.

For me, I physically heal myself with cupping. I do it myself, I do it on others, and I also taught my partner to do it, so we do it on each other. In Lebanon, we drink hot rose water for cramps or the stomach. We work with anise and different types of molasses. CBD is extremely healing for the body—internally and externally—so that’s something I experiment with and look into.

I am pro cannabis. I want cannabis to be legal. Of course, there are issues with cannabis being legal because communities of color are going to be affected first, and they’re not going to be respected. So when we talk about legality you have to first and foremost talk about social justice.

Healing can take any shape or form. It could be a chant, it could be a walk, it could be meditation. I would say that you cannot help anybody unless you’ve helped yourself. You cannot love somebody unless you find self love. You cannot help the world unless you have figured out your own problems, and your own self, in your own community. I really think it starts within.

I feel like my roots are in a terrarium—they’re not planted anywhere.

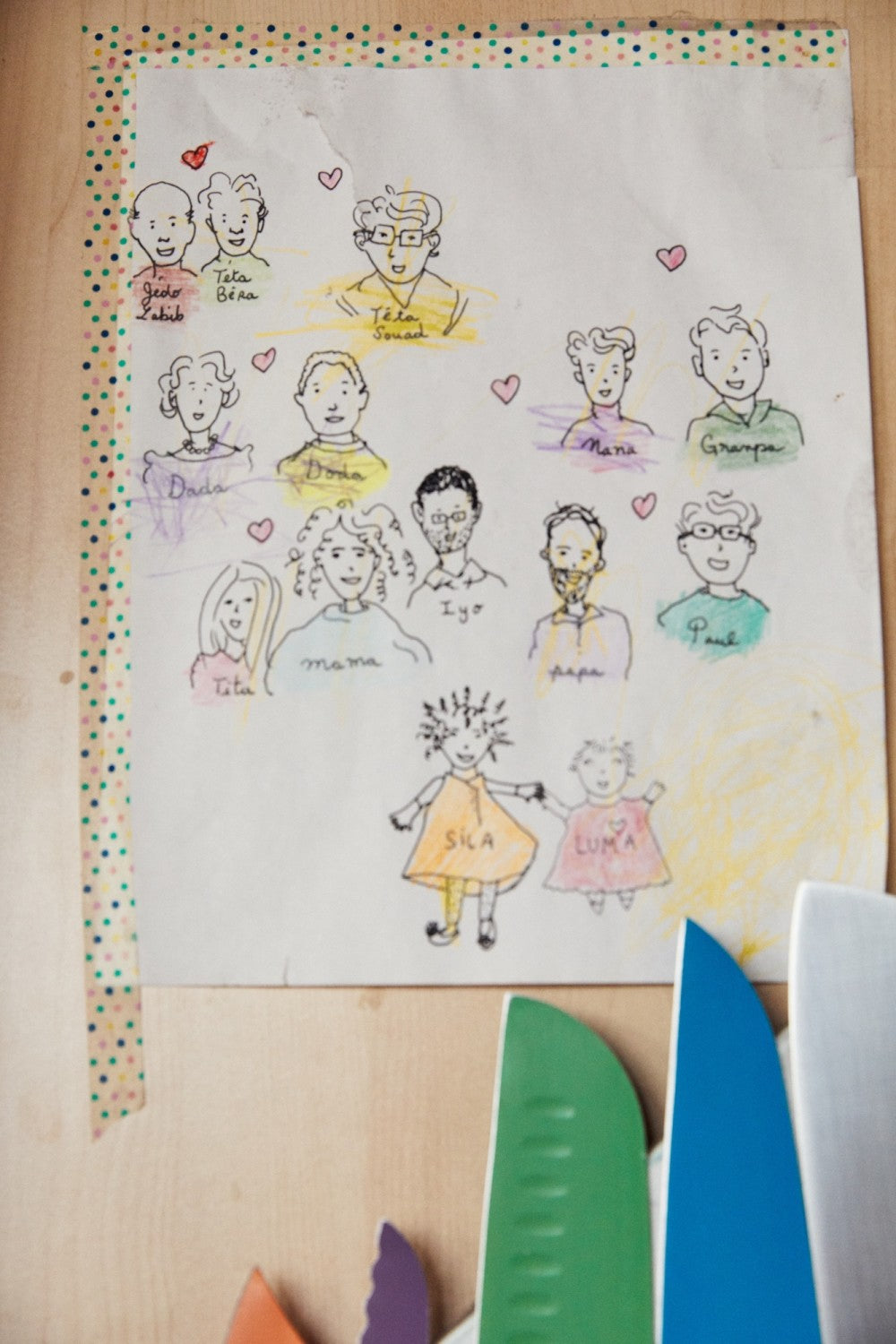

I’ve moved so many times out of necessity. In the beginning, because of the war, then economic necessity, and then to find peace. I don’t own my place now. It’s small and I have two kids, so I will eventually have to move out of here, as well. I feel like my roots are in a terrarium—they’re not planted anywhere. I don’t know if it’s good or bad. If I think of it as bad, I’m going to feel depressed, like I belong nowhere. And I will feel like the other, which I’ve felt my whole life.

But when I accept this, I realize that my perspective is the biggest asset I’ve gained from this experience. This is who I am. Do I want to plant my roots? Absolutely. I really want my roots in the soil. But where . . . I don’t know. There’s nowhere I feel “most at home.”

In Lebanon, my soul vibrates at a frequency that I can never find anywhere else. And in my grandpa’s garden, I feel the most at peace. But can I live there? No. Can I blossom there? No. Can I grow there? I don’t think so.

Here, I can grow in my terrarium, but I fear it’s going to tip and fall and break. I feel this vertigo. I know this is all temporary, but so is the human experience. Nothing lasts. A lot of people who are deeply rooted have a conviction that everything is like this or like that. There’s little room for nuance in the way that they perceive the world. So for me, it’s a blessing and a curse. For sure, I want my roots planted. Maybe that would heal my anxiety, but I don’t know where to plant them.

We are imperfect humans. It’s not possible to be perfect. But what you can be is true. There’s a difference between perfection and truth. Truth isn’t perfect, but it’s beautiful. We don’t lie to our children. If I have to fake a smile or laughter or patience, it’s a lie, and they will sense it. They already sense it and it’s awkward because you are gaslighting them into believing everything is fine when it’s not. They tell me, “Why are you fake laughing?” This is awareness that we want the next generation to have. Emotional intelligence is key to coping with the world around us.

So when I’m upset, I get upset. I’m going to control myself, of course. I’m not going to break a glass or smash a plate. But if I’m upset, I’m upset, and they know I’m upset and they respect it. Just like when they are upset, I let them be upset. I hold space for their tears. They don’t hold space for my upsetness, but they stop, and they respect it. I feel like they have a lot of empathy because they’ve seen me cry.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Céline Semaan photographed by Meredith Jenks at her home in Brooklyn. If you like this Conversation, please feel free to share it with friends or enemies.