Common Citizen's Director of Social Equity and External Affairs on learning to love her size, increasing equity in cannabis, and creating generational wealth.

AS TOLD TO PATTY CARNEVALE

My mom and dad met in college in the Upper Peninsula, at Northern Michigan University. My dad is Black and my mom is white, and my grandparents on my mom’s side were not receptive to my father. My father was a victim of the crack epidemic, so he wasn’t very present in my life. There are a lot of stereotypes surrounding Black fatherhood and my mother’s family held onto those.

Because I was raised by a white mother, one of the first ways that I learned about race was at my grandparents’ cabin. Like they did with all their grandchildren, they put a life vest on me and threw me into the river. I was able to swim, so I couldn’t be Black. That was the way my grandfather accepted me. That was my upbringing. I had to practice erasure of my cultural background. I had to perform in a way that was not stereotypically “Black.”

I was constantly trying to find somewhere I fit, until I realized that I didn’t really fit anywhere. So instead I tried to make my own space.

I was raised in Detroit, which is the Blackest city in America, but we spent a lot of time in the suburbs. I was always the only Black kid in my youth group, in the churches we belonged to, in the restaurants we ate at. But when I was at home in Detroit, I wanted to be a part of the community that was reflective of me.

My grandmother, my father’s mother, was stable, nurturing, and a devout Christian. She would take me to church every weekend. She would buy all of my school clothes. But she is a devout Apostolic Pentecostal woman, and I am queer. On the one hand, she was the most developmentally important person in my life because her love was nurturing, solid, and secure. But also she had her own beliefs that made me feel unloved. I was constantly trying to find somewhere I fit, until I realized that I didn’t really fit anywhere. So instead I tried to make my own space. That really informs the work that I do now, because I just want to make space for everyone to feel like they can be their best and most authentic selves.

I found a lot of joy in school, because I was good at it. I loved math. My dad was brilliant—I was always competing with his school records. Because he was so sick—he was in rehab most of my life—I wanted my grandma to be able to see her lineage and her legacy in me. To show her what he was able to create.

I was always trying to prove myself on both sides. Trying to heal my grandmother while trying to prove to my white family that I was good enough. They are conservative, Republican, military people. I’m a queer, free-spirited progressive who works in cannabis. I spent a lot of time trying to win people over, but I wanted to be able to be myself—to not have to conform to anybody else’s standard.

I identify as a Black, biracial, queer woman who is also a fat woman—a woman of size. I’m pretty fluid in my gender identity and my perspective around gender. I like to lead with social identity markers because they illustrate my experience navigating the world. I am incredibly liberal and progressive when it comes to my politics, and I am an educator, a coach, a mentor, a developer, and a nurturer. I’m a quintessential big sis.

I was looking for an industry that would allow me to use my passion ... to build pathways to generational wealth for my own legacy.

I started my career in educational access work. I worked as a college advisor in Battle Creek, Michigan. From there, I went to Teach for America. I taught for two years in St. Louis. I was still advocating for educational access and sending kids to college, but I started wondering: What happens when they get there? Are they finishing college? Are they just landing in a lot of debt? How is the institution treating them?

So I moved into student affairs, and worked as an administrator at the University of Delaware. I oversaw a strategic plan for supporting underrepresented students, which focused on building welcoming and inclusive learning environments as well as training our staff to be able to support them.

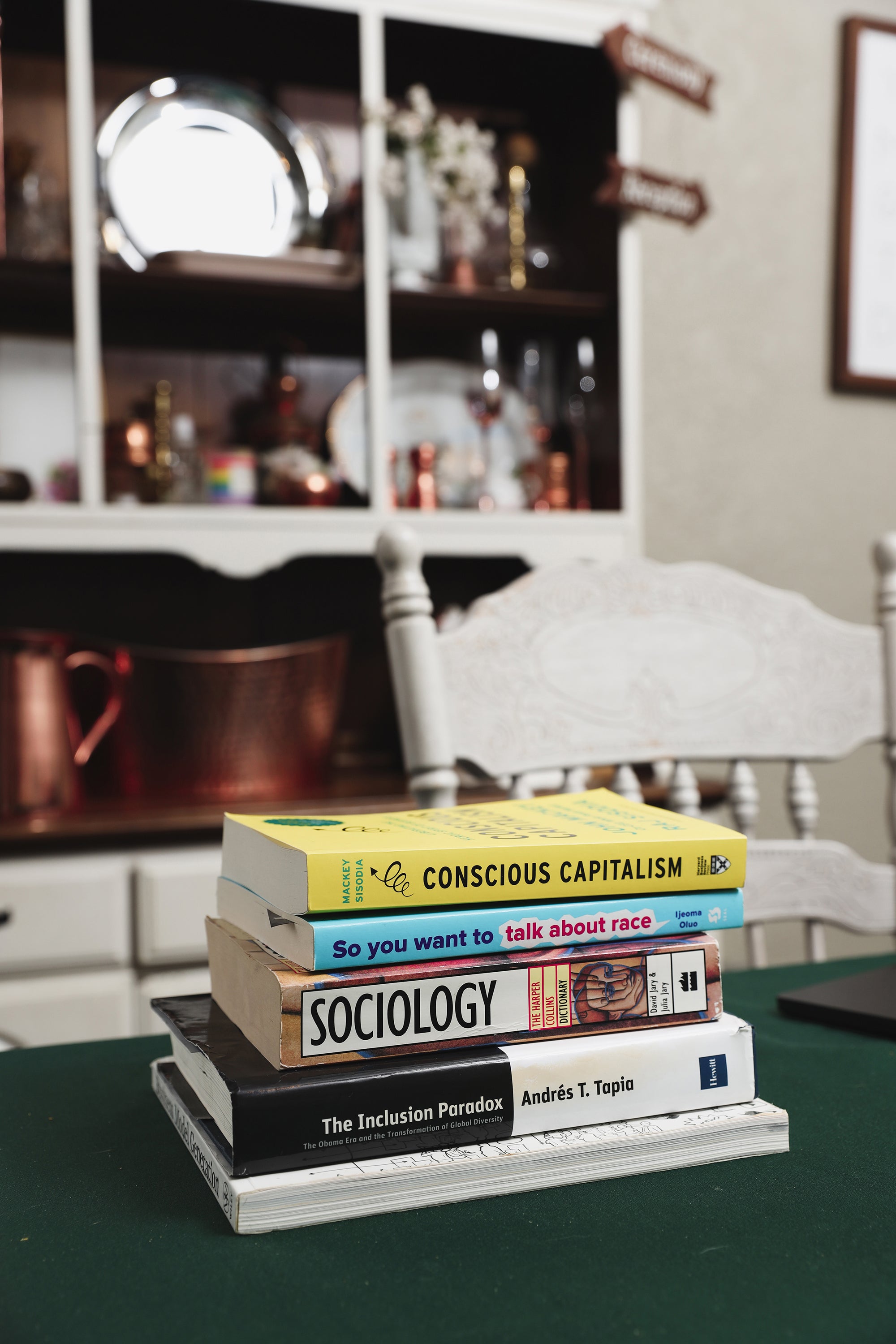

While I was at the University of Delaware, I got my MBA. I then moved into diversity, equity, and inclusion training at the corporate level. I developed a curriculum for cultivating racial equity in the workplace that has now set the standard for the learning and development industry. But I wanted to be an entrepreneur. That’s how I landed in cannabis. I was looking for an industry that allowed me to use my passion for justice, equity, inclusion, and community, to build pathways to generational wealth for my own legacy.

That’s when I met Common Citizen. Being able to transition into a regulated operator and see what this industry can do at scale has been one of the most rewarding learning experiences of my life. I report directly to our CEO, Michael Elias. He has a heart of gold. Mike acts with integrity, and with his values and belief in doing what’s right by patients and by his team. He cares more about the people who work for us than anything.

We have Citizen Culture Groups, which are employee resource groups based around identity. Our Honoring Women CCG, which launched during Women’s History Month, opened a pantry at our headquarters so we can come together to provide canned goods, shoes, and clothing to employees in need. Each month we prioritize different items. Mike wants to make sure if you don’t have a car, we’ll figure out a way to get you a car. If you don’t have a place to live and need to move, he’ll try to figure out how to get affordable housing. He cares about his people. And he inspires me.

But he’s also a businessman. As a leader in capitalism—because that’s the system in which we operate—he does a good job of including other perspectives while also thinking about long-term strategy and short-term wins to support his team. I really respect his leadership and—he told me to stop saying this—I aspire to be a leader like him.

I’ve been able to integrate throughout [Common Citizen's] entire organization and be an evangelist for social equity.

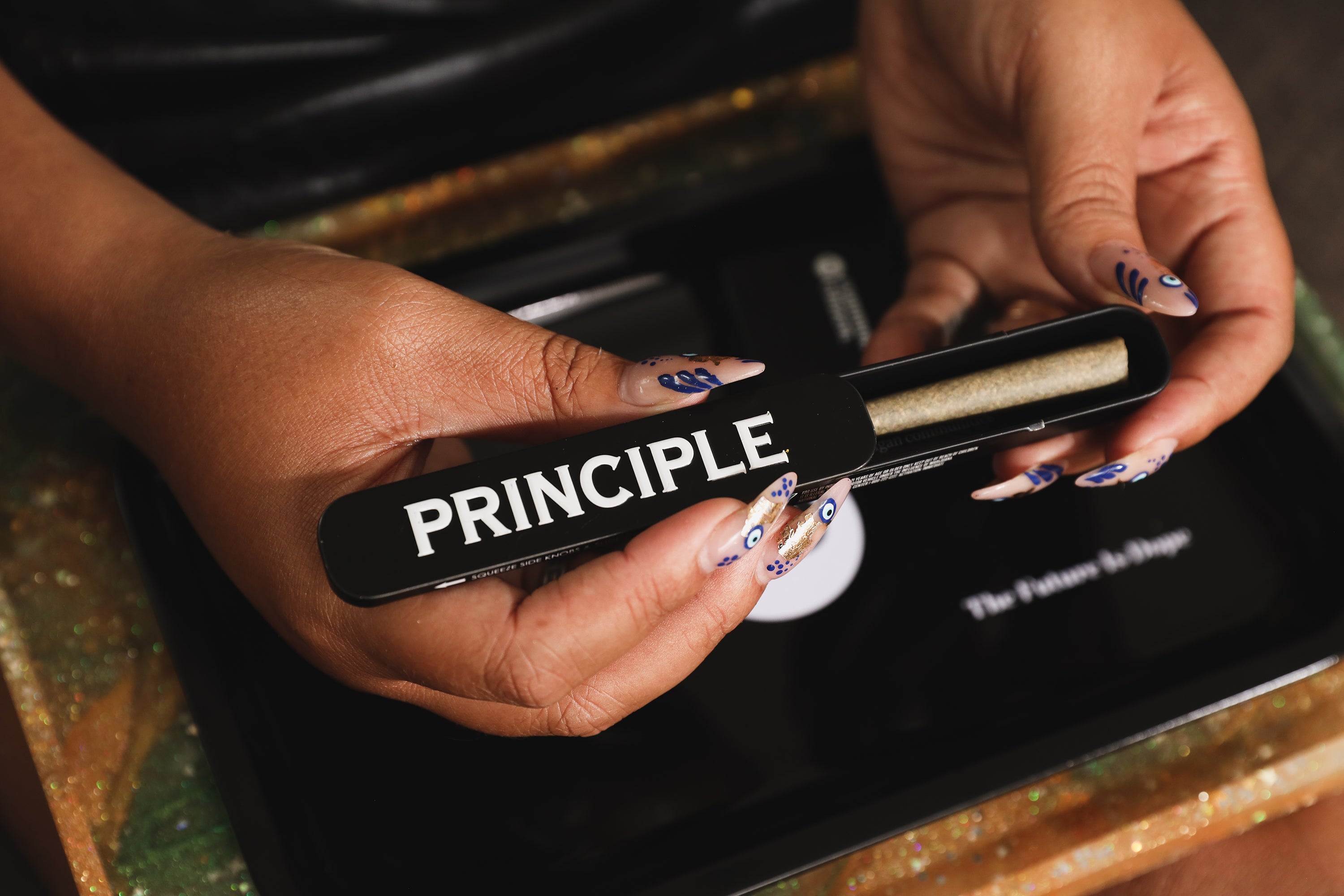

I’ve integrated myself into every value stream, from citizen resources and our recruitment and retention strategies, to how we’re measuring diversity indicators around leadership, to what it looks like to prioritize and offer contracts to diverse suppliers in order to increase the representation of women-, queer-, and minority-owned businesses throughout our supply chain. This also extends to our operations side, which includes our Principle product line, where 100% of our wholesale profit goes into the community.

Common Citizen is the largest vertically integrated wholesale distributor of cannabis flower in the state. We have a huge hybrid greenhouse with over 70 acres of cultivation. We are a grower, we’re expanding our processing footprint, and we have eight retail locations across the state. I’ve been able to integrate throughout the entire organization and be an evangelist for social equity.

With the profits from Principle, I’ve developed three micro-grant programs that distribute funds throughout the state in different communities. The first, For the Culture, focuses on increasing accessibility to the arts. The second, the Principle Community Impact Award, is targeted towards nonprofits that build community-led infrastructure development, political empowerment and expungement, home ownership, and workforce development—the four markers identified by the McKinsey Racial Wealth Gap as key drivers for advancing racial equity around wealth.

Failed startups led by white men raise, on average, $1.3 million. But startups led by Black women receive, on average, about $36,000.

The third, the Common Principle Startup Accelerator, is a prototyping, milestone-based grant. We invite startup-stage entrepreneurs to pitch their ideas for the opportunity to receive business model training and executive coaching. Once they build that model, they’ll be able to implement their prototype using the $5,000 micro grant. And at the end of the year, we’re inviting all of our accelerators to pitch their business model for $50,000.

Failed startups led by white men raise, on average, $1.3 million. But startups led by Black women receive, on average, about $36,000. Our vision at Common Citizen is to reinvest $1.3 million into the community by 2023, and draw attention to those gaps.

We just did a community engagement activation back in Battle Creek, where I was a college advisor, and five of my former students came to learn about our micro grants. I found out that at least one of my former students works in our cultivation. That was a full circle moment for me.

The third, the Common Principle Startup Accelerator, is a prototyping, milestone-based grant. We invite startup-stage entrepreneurs to pitch their ideas for the opportunity to receive business model training and executive coaching. Once they build that model, they’ll be able to implement their prototype using the $5,000 micro grant. And at the end of the year, we’re inviting all of our accelerators to pitch their business model for $50,000.

Failed startups led by white men raise, on average, $1.3 million. But startups led by Black women receive, on average, about $36,000. Our vision at Common Citizen is to reinvest $1.3 million into the community by 2023, and draw attention to those gaps.

We just did a community engagement activation back in Battle Creek, where I was a college advisor, and five of my former students came to learn about our micro grants. I found out that at least one of my former students works in our cultivation. That was a full circle moment for me.

I’m a Pell Grant, full-ride scholarship kid from the University of Michigan who also inherited a shit-ton of debt. I didn’t have a safety net. I was scared of wanting kids, scared that I would mess them up. We’re all going to mess them up in our own ways, but I didn’t want to be violent and abusive. That’s something that comes with the cycle of poverty—rage in the household.

I’m finally at a place where I can say I want some kids. I had a lot of trauma loops and reactions I had to heal. I also now know I’m not going to be raising my children in poverty. I know where I’m headed. I’m going to be able to leave my kids with a legacy. I’m going to be able to provide for them so they don’t end up in the same place I came from. Coming to that realization has been transformative.

Where I’m at right now is building sustainable healing habits so that when the kids come, my partner and I will be able to teach them the same. For me, that means a lot of movement practice, getting my body in shape to be on the ground, playing with my children, being present.

I’m embracing that God blessed me with this big body because I’m meant to take up space. Clothes and adornments play into those things. I’m six feet tall. I never wore heels. Then when I was in California at The Smoker’s Club Festival in L.A., I went to a swap meet and bought two pairs of kitten heels. And I was like, Okay, I’m going to learn to wear these shoes. Because I’d been telling myself I couldn’t wear them because I’m already tall. But now I’m walking in whatever. Just playing and trying to learn to walk in them, playing with how I dress, learning my style.

My Curvy Cannabis Series—a campaign to increase the representation of fat women in cannabis marketing, which also provides a space for healing and connection—was one way I learned to be able to see myself, look at myself, and love myself. We did boudoir photo shoots that centered cannabis products, but a lot of the facilitative dialogue that happened were women sharing stories of trauma.

A lot of my healing has been around the idea that I’m here to take up space, and I don’t have to be invisible.

I never wore lingerie before I did Curvy. The most impactful moment for me was when I was looking at myself in the lingerie, and I was like, “Look at how my armpit fat hangs over. I hate it.” I asked my friend, “Do you have this?” And she was like, “I don’t have that, but I have this.” She had the wings. There are all these things that we’ve been taught to hate about ourselves, and we all have our thing, but here we are looking stunning, there to celebrate each other. It has taught me to embrace my body.

Curvy is actually kind of how Common Citizen found me, because we were featured in their documentary Somewhere Higher. I was able to pay 10 plus-size models through that. Even though over 60% of women are size 14 or up, we’re only included in about 2% of marketing. We’re less likely to get gigs. We’re less likely to be included. We are literally taught to be invisible.

A lot of my healing has been around the idea that I’m here to take up space, and I don’t have to be invisible. It’s about embracing yourself in all of your fullness. I had to teach myself to love myself. I don’t care how you view me anymore. It’s about how I view myself.

I think that in order to be courageous you need to be authentic and true to who you are. You have to be very clear on what your values are, what you want to accomplish, who you are, and behave with integrity in staying true to those things. To me, courage is acting with integrity around who you are in every space.

I think the core of how I take care of myself is knowing how valuable I am.

My idol in this industry is Mary Pryor. I think that she has the most courageous, strong, and clear voice. She’s not going to tolerate BS. She’s going to be very direct about what’s right and wrong. She’s cultivating pathways for so many people who are unseen and unnoticed within this industry. I really value her intention, thought, and care for our community. She reaches back. She’s not in Detroit—she’s in New York—but she reaches back and makes her presence known. We have a Black Women in Cannabis Facebook chat, and she engages there to let folks know she’s an available resource. I really value what she stands for and how she does her work. How freely she gives herself to ensure her mission of increasing inclusion in the industry. And how she moves. She moves fast.

My community is my support system. Oftentimes people say that as you elevate, you lose relationships—and I’ve gone through a lot of transitions in mine—but there are consistent people who pour into me, love on me, and celebrate me, and it’s reciprocated. Having those relationships helps me stay balanced and recognize that sometimes it’s about the people around you and not necessarily always about the work that you need to get done.

I think the core of how I take care of myself is knowing how valuable I am. When I was young in my career, I overworked myself and didn’t know how to communicate my boundaries. I had imposter syndrome. I always needed to be performing. I needed folks to see how valuable I was to them, because I didn’t see the value that I had already in me. I had to learn that I need to fill myself first.

That means getting my mind and my spirit right so that I can be grounded. I’ve started to prioritize better eating and nutrition to make sure that I’m giving myself energy so that I’m not exhausted. I move right, making sure that I’m increasing my flexibility, stamina, and strength in my body.

Another big part of that balance for me is maintaining therapy. I microdose psilocybin. I was doing it every three days, but started doing it daily to make sure that my mind is just ready and wired and intact. If all of those things aren’t integrated, you’re not going to experience joy in your journey. It’s going to feel like work and labor.

Everything I do is what I was brought to this world to do, and an opportunity to make an impact at the scale I’ve always wanted to. I get to have a lot of fun in what I do, and I’m kind of like a celebrity at work. They treat me with respect. They value my perspective—and I work to win them over—but we’re a team, and I love it. I’m living the dream, honestly. I wake up happy.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Jess Jackson photographed by Bre'Ann White in Detroit. If you like this Conversation, please feel free to share it with friends or enemies. Subscribe to our newsletter here.